But each year, Congress intervened to save these missions. OCO-3 launched on time in 2019. PACE and CLARREO took some budget cuts but are still set to launch in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

“I’m happy to say it hasn’t been as bad as I thought,” says Andrew Kruczkiewicz, a researcher at Columbia University who uses Earth observation data to assess disaster risk. “Maybe that’s just because the expectations were [that things were] going to be a lot worse.”

The administration tried some other tactics to weaken the impact of climate research. Scientists were pressured to stop using phrases like “climate change” and “global warming” in any grant proposals or project descriptions. And some institutions, like NOAA, were stocked with climate critics who have downplayed climate change.

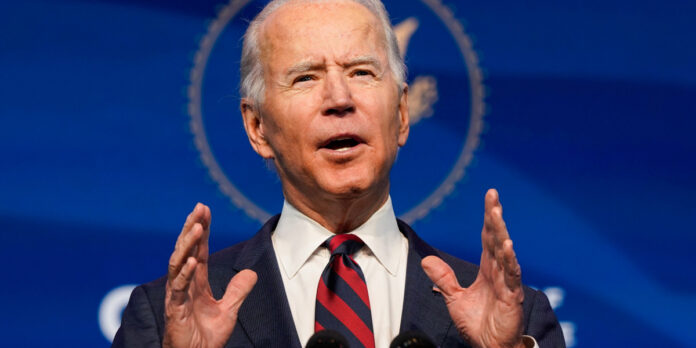

So the most immediate steps the Biden administration could take on day one would be to free scientists from any language restrictions, and to assure Earth observation mission teams they have leadership’s support to plan long-term investigations in order to get the most out of these missions.

The short steps

Increased funding would help expand the scope of these types of programs to collect more valuable information. More money could be used to plan and launch new missions as well. Mariel Borowitz, a space policy expert at Georgia Tech, thinks it could be worth taking a cue from the European Space Agency and launch an Earth observation program similar to Copernicus, which is tasked with studying global climate trends over a very long period of time. This could be a nice contrast to the current NASA approach of using discrete missions to investigate specific research questions over just a few years.

Other trends under Trump’s watch cannot and probably shouldn’t be reversed, but they will require a response. For example, any programs spearheaded by private companies like Planet Labs (which operates hundreds of EO satellites) have found room to grow more rapidly in the last four years than ever. New companies are not only building their own sensors and flying hardware in orbit, but also processing data and disseminating images. NASA still has the largest Earth observing system in the world, and its data is free for anyone to use. But there may be communities or regions of the world whose only access to the relevant data may come from private parties who charge for it.

The Biden administration could take steps to permanently ensure free and open access to what NASA collects, and it could also look into engaging with the private companies directly. “There’s already a pilot program started where NASA purchases the data from commercial entities under a license that allows them to share that data with researchers or a wider audience,” says Borowitz. It may be a good model for Biden to lean on permanently to help a private industry grow while giving less-wealthy parties access to critical data.

“EO data is different from other types of data,” says Kruczkiewicz. “In some ways, it’s one of the most privileged types of data.” Maintaining its status as something closer to a public good may ensure that people continue to treat it as privileged.

But there are other large questions about the future of Earth observation research that the scientific community is ready to resolve. These have less to do with remediating the impact of the Trump years and more to do with understanding how we can better apply the findings of climate science in the real world.

“I feel like we have an opportunity to rethink things,” says Kruczkiewicz. “The past four years have forced us to think about not only the way that data is produced, but who has access to it, how it’s disseminated, what are some of the unintended consequences for these programs, and how far down the line we should be accountable for as scientists.”

Beyond missions

Simply throwing more money at Earth science and EO programs isn’t enough, though. First, “these satellite programs take an incredibly long time to develop, fund, and implement, so the time frame for them is generally outside the length of individual administrations,” says Curtis Woodcock, an Earth scientist at Boston University. The effects of Earth science cuts at NASA during George W. Bush’s administration are still being felt, Woodcock points out: “In many ways NASA earth science has not completely recovered since then.” To restore Earth science to rigorous levels, we need a long-term plan that will go beyond Biden’s first (and possibly only) term.

Second, there is already a lot of Earth observation data that we can already use—we just need better processing tools. “My fear is that the gap between data availability and use of that data is growing because we have so much data now,” says Kruczkiewicz. “We don’t necessarily need to develop new technology to have new sensors, or new spatial resolution in order to solve flood questions.”

The types of technologies federal officials may want to start investing in, instead, are data processing and tasking systems that can analyze and make sense of the enormous amount of imagery and measurements being taken. Those tools could, say, illustrate which communities might require more resources and attention should a flood or a drought strike.

Third, we need to start thinking about how climate science is applied on the ground. For example, Kruczkiewicz’s own work involves using satellite data from NASA to understand the risks vulnerable populations and communities face from disasters like floods and wildfires, as well as the issues involved in preparing for and responding to such events. “I think we need to rethink the stories that we tell of people on Earth benefiting from EO data,” he argues. “It’s not just about throwing flood maps over the fence and hoping people use them.” The Biden administration could start taking steps to empower humanitarian organizations that can communicate what EO findings mean, how they can be turned into practical strategies, and how the data could help resolve social inequalities exacerbated by climate impacts.

Other institutions outside the US have done a better job getting up to speed on this type of perspective. Dan Osgood, an economist at Columbia University, uses satellite data for insurance programs that pay benefits to African farmers who face the threat of crop loss due to climate change. He and his team are already learning how farmers use these payouts to invest in higher-return agricultural approaches. It’s an example of how EO data doesn’t just tell us something new about the climate but can be used to actually create societal change.

“It used to be that the US government was investing in us to try and do that kind of validation,” he says. “And now, for more than four years, it’s been primarily European governments. ESA’s data is much more freely available, and they’ve invested in us to be able to use it. The European products are often easier to work with and, in many cases, less problematic.” (Osgood notes that much of the change he describes had its beginnings late in Barack Obama’s administration.)

Many of the actions Biden can take with respect to Earth observation might do the most good by simply setting a tone for how the US wants to treat climate data. Encouraging open access, so the information can be shared with the world, could go a long way to reorienting the US as a leader against climate change.